Almost all of the resumes that I come across for junior roles either consist of lab experiences at the same university the students attend or summer internships at a prestigious academic research institute. Then, there are those rare resumes that include internships or cooperative education (“co-op”) programs adding up to more than one year of industry experience. So why do the latter resumes stand out more? Why is a student performing PCRs at a university viewed as less competitive for the same role as a student who performed PCRs at a biopharmaceutical startup? Isn’t a PCR a PCR?

The Difference Between Industry and Academia

The difference has its roots in the larger perspective: industry versus academia. To put it simply, academic focuses on the research side of Research and Development and industry emphasizes the development aspect more. There are distinctly different rules, regulations, hierarchies, and most significantly, objectives. Any scientist will tell you whether in industry or in academia that lab work is never just about the hard skills you accumulate. Co-op programs have a significant upper-hand as they are usually formally set-up agreements between universities and companies. But, the true benefit of co-ops comes from their structure. Students can complete academic research while attending class that semester and then hold a several month spanning job in an industry. Moreover, those industry positions come with the opportunity to perform the exact skills in the exact environment that entry-level positions are looking for in applicants.

The other issue is the overwhelming amount of entry-level applicants who only have academic experience. Why wait until after college to gain industry experience? Well, there is a minority of industry internships as compared to the abundant academic research volunteer and paid positions. It is just easier to find an academic position when you’re in an academic institution. It’s also just as easy to receive no guidance or mentorship regarding a career in industry when the potential mentors surrounding you have already established academic careers. There is a burgeoning difference in how young professionals approach their careers and the job market than their predecessors. So, apply the principles of good science to your own life. Formulate questions that you gather research on to answer. What is a career in academia or industry look like? Which would I prefer? What is the difference? What are the positives and negatives of each? Reach out to a wide range of people who occupy jobs that you could see yourself enjoying. If they cannot provide you with what you need, ask them for a reference to another professional who can. You deserve to make an informed decision.

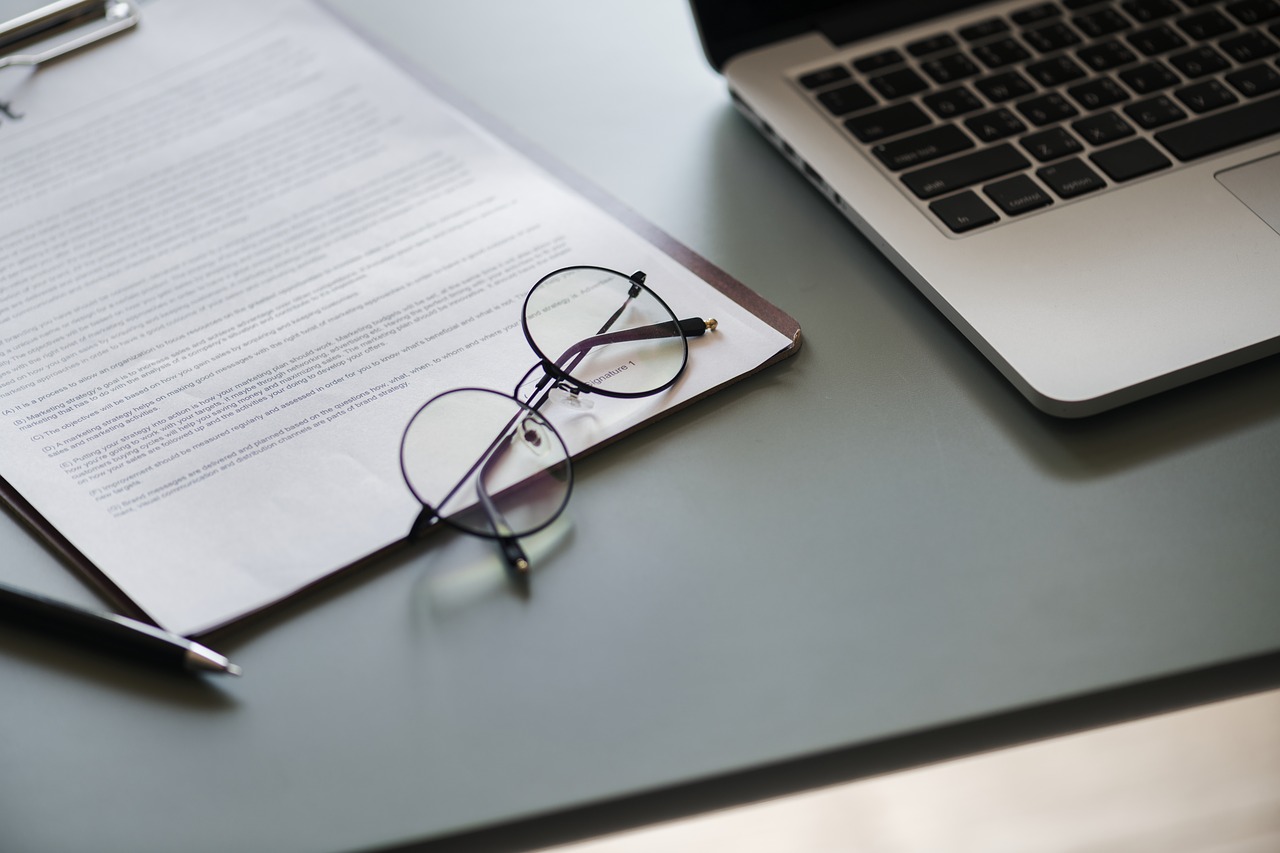

Seeking the Best Job for You

The job market is both specialized and diverse for junior roles. You can always forge your own path and there is sure to be a position out there that suits you. How do you find it? Apply to a plethora of positions – but be job-specific for each one. Sending the same resume for five different jobs is an inefficient, and quick way to eliminate your application from four out of five of those roles. For each application, compare and contrast the job description with your own skills and experience. Put all the matching components at the beginning of the resume or make sure it stands out – whether highlighted or underlined – throughout the resume.

Gathering information and networking is preliminary to the action step. Structure your college years in a way where you can provide yourself with the most options later. If you’re working during the semester at a professor’s lab, then consider spending the summer completing an industry experience. But, most importantly, ensure that you are getting the absolute most you can out of both experiences: learn, observe, and expand your skill set to match the job you want later on in your career.